What You Need to Know About Iran and Venezuela Before Next Year

US President Trump struck both Iranian and Venezuelan land for the first time in 2025. Neither regime is safe as they enter 2026.

For Western media, both Caracas and Tehran are coverage blind spots. If networks are let into the country, reporters are escorted by government minders who control what they see. Sky News was recently able to report in Venezuela; the ‘Maduro-strong-man’ message the regime was looking to send still came through loud and clear; their access included a lawyer representing thousands of political prisoners.

Here at News with Suz, we’re grateful to have a source in Iran who has sent us this despatch. For their safety, we are protecting their identity.

TEHRAN (H2H) — From the outside, demonstrations in Iran are often described as eruptions—sudden, dramatic moments of defiance that flare up and either succeed or disappear. From the inside, they feel very different. They feel slow. Heavy. Accumulative. Like pressure that never fully releases.

The reasons for this are layered, but the most immediate is economic. Iran’s economy is now widely experienced as being in a state approaching hyperinflation. Since the brief but consequential twelve day conflict with Israel, the national currency has lost nearly half its value. For ordinary Iranians, this is not an abstract statistic. It is felt daily—in rent, food prices, transportation, and the shrinking ability to plan even a few months ahead.

What people are experiencing now is not a single protest movement but a sustained state of confrontation between society and the forces tasked with controlling it. These are mixed protests: merchants in the bazaars, university students facing a future with diminishing prospects, women demanding autonomy, and ordinary men and women struggling to make ends meet.

The streets are only one part of that confrontation. The rest unfolds in homes, cars, voice notes, and social media stories.

This round of protests is not primarily about police brutality or a single triggering event. It is about quality of life—and the growing gap between what people experience and what they believe they deserve.

Iran holds the world’s second-largest natural gas reserves and the fourth-largest oil reserves. And yet, its cities endure regular power cuts in both summer and winter. Iran has extensive coastlines, but many of its cities face severe water shortages. The country began manufacturing cars in the 1960s, yet today produces vehicles with emissions standards that would be considered outdated even by 1980s benchmarks—contributing to Tehran and other major cities being among the most polluted in the world.

For many Iranians, this contradiction has become intolerable. Resource abundance paired with daily dysfunction is no longer explained away as temporary mismanagement. It is experienced as structural failure.

For years, the Iranian state relied on ambiguity—on blurring the line between authority and legitimacy, between order and consent. That ambiguity is eroding.

The divide is no longer abstract. It is physical and visible, embodied by the Basij and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps on one side, and civilians on the other.

This moment is no longer framed by many protesters as reform versus conservatism, or policy versus ideology. It is framed as dignity versus humiliation.

When protesters shout “bi-sharaf”—you have no honor—at police or Basij units, they are not debating laws or governance models. They are attacking the moral foundation of authority itself. Honor carries deep cultural weight in Iran. To accuse someone of having none is to deny their legitimacy at the most personal level.

That accusation resonates because exhaustion has set in. People are not only angry. They are tired.

In several cities, chants of “Javid Shah”—long live the Shah—have re-emerged. This is not nostalgia for monarchy in any literal sense. It is provocation.

The slogan functions as a psychological weapon aimed directly at the ideological core of the Islamic Republic. It says: you have failed at every level of governance.

For many Iranians, the comparison is not ideological but practical. Under the late Shah, people felt pride in saying they were Iranian. Iranian passports were widely respected. In 1978, the unofficial exchange rate stood at roughly seven tomans to one U.S. dollar. On the day these protests erupted, that rate had fallen to around 145,000 tomans to the dollar.

The chant is not a blueprint for the future. It is a rejection of the present.

What many people feel is not revolutionary fervor, but exhaustion mixed with resolve. A sense that retreat is no longer psychologically possible, even if progress remains slow.

The Basij and IRGC are no longer abstract institutions in the public imagination. They are present—on motorcycles, in vans, at intersections, and in neighborhoods where they were once invisible.

Their presence is meant to deter. Instead, it has clarified the terms of engagement. Unlike previous protest waves, where people fled from the security apparatus, many now stand their ground—shouting insults directly into the faces of those sent to intimidate them.

Demonstrations do not end because people are convinced. They end because the cost is assessed in real time—arrests, beatings, disappearances that rarely make international headlines.

And yet, they keep happening.

Outside Iran, demonstrations are often measured by size, frequency, or outcome. Inside Iran, they are measured by persistence.

Each protest, even when suppressed, alters the psychological terrain. Each chant changes what feels sayable. Each confrontation redraws the invisible boundaries of power.

Foreign observers often look for turning points. Inside Iran, people recognize something else: accumulation.

What defines the current moment is not explosion, but frustration, exhaustion, and essentially the delegitimization of the Islamic regime as the rulers of Iran.

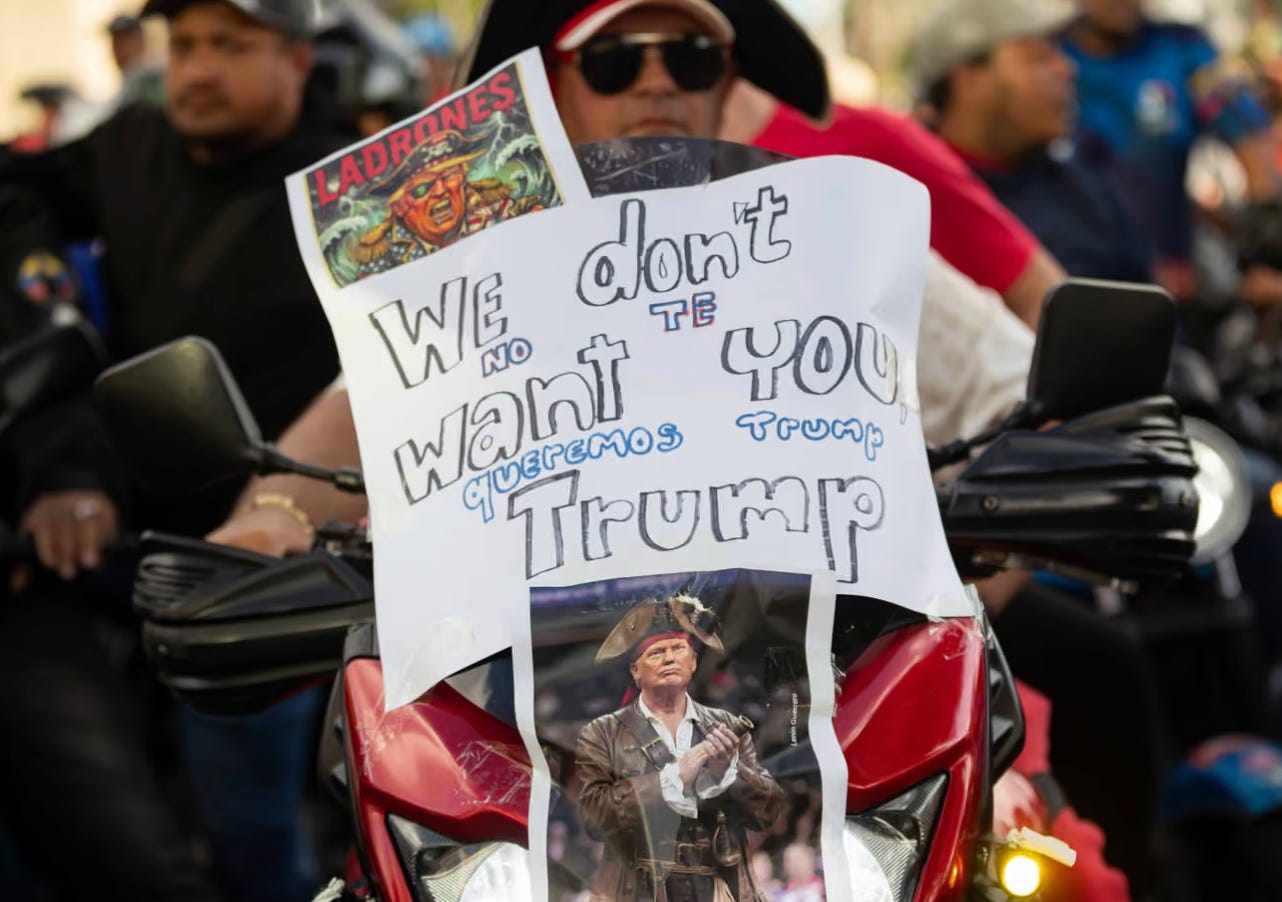

VENEZUELA

Sources from Caracas are proving to be a more difficult get; they are afraid to speak. Contacts in the diaspora tell us: “People are getting detained just for having photos of support to Maria Corina Machado or random text messages.”

It’s been revealed the CIA carried out the first U.S. drone strike on Venezuelan land, targeting a cartel-linked port facility, an operation publicly acknowledged by President Trump.

So what’s this all about?

Trump Says Venezuela Stole “U.S. Oil.” The History Is More Complicated.

When Donald Trump announced a “total and complete blockade” of sanctioned oil tankers entering and leaving Venezuela this week, the justification was sweeping. Venezuela, he said, had stolen U.S. oil, land, and assets, used those resources to fund crime and terrorism, and must return everything immediately. He went further, labeling the Maduro government a “foreign terrorist organization” and ordering U.S. forces to enforce the blockade.

A day later, Homeland Security advisor Stephen Miller sharpened the claim. In a post on X, he argued that “American sweat, ingenuity and toil created the oil industry in Venezuela” and that its nationalization amounted to “the largest recorded theft of American wealth and property,” later used to fuel drugs, violence, and terrorism inside the United States.

It is a dramatic accusation, delivered alongside a dramatic show of force. The U.S. has assembled its largest military presence in the region in decades just off Venezuela’s coast and has carried out multiple strikes on boats it says were trafficking drugs, killing about 90 people since September. The administration has not publicly released evidence tying those vessels to drug trafficking, prompting critics to argue that the real objective is oil leverage and pressure for regime change.

To understand whether the United States has any real claim to Venezuela’s oil, you have to rewind more than a century.

U.S. companies did, in fact, play a major role in building Venezuela’s oil industry. In the early 1900s, American and European firms began drilling across the country. In 1922, vast reserves were discovered at Lake Maracaibo, initially by Royal Dutch Shell. American companies like Standard Oil soon followed, developing infrastructure under concession agreements that turned Venezuela into one of the world’s top oil exporters and a critical supplier to the United States.

That early dominance is what Miller is pointing to. But development is not ownership.

In 1960, Venezuela became a founding member of OPEC, asserting its role as a sovereign oil power. Then, in 1976, amid a global oil boom, the country nationalized its oil industry under President Carlos Andrés Pérez and created the state-owned company Petróleos de Venezuela, or PDVSA. Foreign companies lost control of production but were compensated under the laws of the time. Similar nationalizations happened across the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America during the post-colonial era.

From an international law perspective, Venezuela was on solid ground. Under the principle of Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources, recognized by the United Nations in 1962, sovereign states are entitled to own and control the natural resources within their borders. That principle is clear: Venezuela owns its oil. The U.S. has no legal claim to it.

The relationship deteriorated further after Hugo Chávez took office in 1998. His government seized additional foreign-owned assets, restructured PDVSA, and prioritized political goals over efficiency. Production declined amid mismanagement and underinvestment. U.S. companies lost billions, and resentment hardened in Washington.

Sanctions followed. The U.S. first imposed oil-related sanctions in 2005 and expanded them significantly in 2017 and 2019 under President Nicolás Maduro. Those measures cut Venezuela off from U.S. markets and the global financial system. Oil exports to the U.S. nearly stopped, pushing Venezuela to sell primarily to China, with smaller flows to India and Cuba.

Today, Venezuela still holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, estimated at 303 billion barrels, mostly in the Orinoco Belt. Yet its output has collapsed. In 2023, it exported just $4.05 billion worth of crude, a fraction of what major producers like Saudi Arabia, the U.S., or Russia earn.

Chevron is the lone U.S. company still operating there, under a special license that allows it to partner with PDVSA in exchange for a share of production. Chevron accounts for about one-fifth of Venezuela’s official oil output and has billions of dollars in infrastructure on the ground. Leaving would likely mean losing those assets entirely, as happened to Exxon, Cargill, Hilton, and other foreign firms during past nationalizations.

Against this backdrop, Trump’s blockade marks a sharp escalation. By framing Venezuela’s oil as “stolen American property,” the administration recasts economic pressure and military enforcement as asset recovery rather than intervention. It is a politically potent argument, especially for audiences unfamiliar with the history.

But legally, it does not hold up. Venezuela’s nationalization may have been disastrous for its economy and devastating for foreign investors, but it was not theft under international law. The oil belongs to Venezuela.

The real question now is not who owns the oil, but how far the United States is willing to go to control its flow, and what precedent that sets when military power is used to enforce economic claims dressed up as moral ones.

Sources: Axios, Aljazeera, and The Hill